Tula Read online

PRAISE

What they say about the film:

‘Indispensable! Gripping!’ Algemeen Dagblad

(AB Zagt)

‘A must see’ Metro

‘A fascinating drama about a heroic man who lived in a time that deserves more films.’ Spits (Marieke Kremer)

CLICK HERE TO WATCH THE TRAILER:

For Max, Mees and Linde

Contents

Praise

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

XXII

XXIII

XXIV

XXV

XXVI

XXVII

XXVIII

Epilogue

Glossary

Sources

About the Author

Copyright

Acknowledgements

My gratitude is due to all those who read with me and offered comments during the writing process.

Particular thanks to Pacheco Domacassé, for those beautiful and moving stories about the history of the local population of Curacao and for bringing colour to an otherwise grey past. Also, thanks to Charles Do Rego for casting an expert eye on the historical accuracy of the actual events, to Jacob Gelt Dekker, for such wise advice on the plausible character development of Tula and to Charles Grootens for his encouraging yet critical comments on this first ‘product of my pen’.

And lastly, to my parents, for a sun-filled youth on Curacao and for the special relationship it created with this exceptional island.

Foreword

The world at the end of the 18th century is one of enormous unrest with a longing for freedom and self-determination. America tears itself free of England in 1776, and the French Revolution rocks Europe less than two decades later in 1792. The Republic of the Seven United Netherlands has just concluded its final war with England, but the Republic is deeply divided and mired in an internal conflict between the Patriots and the Royalists. The conflict is settled in 1795 in favour of the Patriots. The French occupy Utrecht, the last bastion of the Royalists. The Batavian Republic under French administration is now a fact and Willem V flees to England. France declares war on his country of refuge.

But the unravelling of the established order is not only a feature of European life. In South America and the Caribbean, resistance against colonial domination is rapidly gaining ground. The most significant revolt takes place in Haiti – in those days a French colony – where the slaves take control after a violent and bloody conflict.

Curacao is a small island in the Caribbean, roughly fifty nautical miles off the coast of Venezuela. In the 18th century it is an important port of transit for slaves destined mainly for Spanish colonies. As a trading post of the Dutch West India Company later to fall under the authority of the Dutch Republic, the island is thus a central pivot in the transatlantic slave trade. In total, the Netherlands of the day was responsible for the transportation of close to 550,000 slaves, with more than 100,000 reaching their final destination via Curacao. The ships of the Dutch West India Company transported slaves from Africa across the Atlantic Ocean. The slaves disembarked on the island of Curacao where they were inspected, divided up according to their capacity to work and then sold on to traders. Those who were too weak to continue the journey remained on the island to regain their strength, while the remainder were transported to their final destinations and put to work on the major coffee, sugar and cotton plantations.

Curacao also had its own plantations in those days, but they were not large commercial enterprises. The soil on the island was not particularly fertile, and the dry climate meant that local production was barely enough to provide for the needs of the local population.

In the turbulent years towards the end of the 18th century, trade in the region has almost ground to a standstill. The last ship with African slaves on board sails into the harbour in 1778. As a trading post and international transit station, the negative effects of increasing global tension at the end of the 18th century are particularly tangible on Curacao. It is against this background that the following events take place.

I

‘Not too deep. Come, out of the water, we’re going home.’ The boy pays no attention and dives back into the azure blue ocean.

‘Out of the water this instant! We have to get home. It’s almost sundown.’ There’s authority in his mother’s voice so he does what she says. He lets her dry him off.

‘Was it nice?’ she asks.

‘Really nice, mama, but longer would’ve been even nicer,’ he says and grins as he gets dressed.

They walk hand in hand up the steep path from the beach. The contours of a manor house can be seen in the distance. The woman turns when she reaches the top of the hill and gazes at the setting sun, at the strips of light it casts on the surface of the water. A bell starts to ring. The boy tugs impatiently at his mother’s sleeve.

‘Come, mama, it’s getting dark. We have to go.’

II

Five years earlier

‘Sit still, sweetheart. How can I fix your pètji if you won’t sit still? Don’t you want to look pretty tonight?’ Speranza’s mother whirls around her in a tizzy. ‘Let me look at you. You’re such a picture!’

‘It’s much too warm, mama. Can’t I take this off?’ She points to her colourful saya koe yaki. ‘Nobody wears a jacket in this heat!’

‘You’re nervous, sweetheart, that’s all,’ her mother answers. ‘Now sit still for just one minute. I’d be hot and bothered too if I was in your shoes. Such a good looking man!’

Speranza’s little sister runs giggling into the cabin. ‘Everyone’s waiting. Aren’t you coming outside?’

The village is perched on the slopes of a valley just behind the crest of a hill. Mud cabins with palm-leaf roofs are lined up side by side. Narrow dirt tracks criss-cross the village and converge in a single open space, the place where the villagers gather around the fire in the evening to eat, sing songs or simply rest after a hard day’s work. A group of men huddled near the edge of the gathering space laugh and push one of their number forward.

‘You’ll have to do it, Tula. If you want to keep her at least.’ Louis treats Tula to a fake grin. Tula isn’t comfortable in his starched kalambé. He’s also borrowed his father’s hat, but it’s a little small and it’s perched awkwardly on the back of his head.

Speranza steps outside. A group of women are waiting in line on the narrow path in front of her cabin and when they catch sight of Speranza they start to hum gently. A man with a tambu beats his drum and sets the rhythm as the group start to sway and quietly sing.

‘She’s coming! Don’t just stand there like a dope. If you’re not careful she’ll turn you down.’

‘That’s enough, Louis. Leave the boy alone,’ Jorboe barks. The village’s senior elder can be strict when he has a mind. ‘Come, Tula. Are you ready?’ he shouts to his son.

‘Of course he’s ready… mmm, such a pretty girl.’ Rosita grabs Tula by the arm. ‘Come, boy, walk behind us.’ Jorboe and his wife slowly make their way to the centre of the gathering space. Tula grabs his brother Quaku by the arm, hauls him to his feet and treats him to an enormous smile. Quaku limps along with difficulty at Tula’s side, dragging his left leg as if it wasn’t part of his body. His face seems frozen in a permanent, crooked grin and his mouth, as a

lways, is half open.

When they reach the middle of the gathering space, the tambu player appears on the opposite side and makes his way towards them. Speranza walks behind him, arm in arm with her mother, and they too make their way to the middle of the gathering space. Finally, Tula and Speranza are standing side by side facing Jorboe who peers over their heads at the sky as the sun slowly spreads its fiery-red glow. The ceremony is short. Jorboe briefly addresses the two young people standing in front of him and seems to be in a hurry all of a sudden. Speranza is radiant, and she’s having a hard time keeping her eyes off the wiry, well-built man at her side. Tula also seems happy. When Jorboe has said what he has to say, Tula and Speranza turn, look into each other’s eyes, take each other’s hands, embrace. Jorboe in turn takes their hands and lifts them up: ‘Tula and Speranza. May God guide them on this journey they have chosen to share.’

The tambu player beats his drum and the women break gently into song, a new song. Tula and Speranza make their way through the assembled villagers, who automatically give way to allow the couple to pass. Arm in arm they cross the gathering space and disappear down one of the narrow paths that lead away from it. At the end of the path, a small cabin is bathed in the glow of the evening sun. The palm leaves covering the roof are still green, and the dark, mottled clay on the walls betrays that the little house is only a few days old. Tula and Speranza turn when they reach the doorway. At that precise moment the beat of the tambu ceases. The couple bow and disappear into the cabin. A bell rings in the distance. Night has fallen.

III

Life is hard on Kenepa plantation. The men are expected to give their all day after day, but the sun is merciless, driving temperatures well into the thirties at its height, and the soil dry from lack of rain. A long line of people winds through the field from a well on its edge. Buckets of water are passed from one to the other and emptied out onto the arid surface. Tula and Louis work side by side, using a chapi to dig long channels in the rocky ground and plant new cuttings.

‘Master can’t make up his mind. One day it’s sugarcane, the next day corn, and now he wants to plant indigo.’

‘He’s not interested in what you think, Tula, you can be sure of that.’ Louis slaps Tula on the shoulder. ‘Come on, man. Talk won’t get you anywhere round here.’

Typical Louis. As long as Tula’s known him he’s never had much to say, and conversation is close to impossible. If something bothers him he uses his fists. When they were young and the bigger children in the village tried to pick on them, Louis would wade in and give them a hiding. You could always rely on Louis.

‘Maybe we should ask the bombas what all this is good for. Everybody knows that it takes time to raise crops.’ Tula wipes the sweat from his brow. ‘Everything grows at its own pace, you just need to be patient.’

‘The bombas…’ Louis sneers. ‘The master’s little minions? They’ll do anything to keep their fancy jobs, so you can forget it. Anyway, the only language they know is the lash, and there’s no answer to the lash. If you want it different you’ll have to fight for it.’ He nods knowingly and stabs hard at the soil with his chapi. Tula shakes his head.

‘Fighting isn’t the answer, my friend. Our real strength is in our soul, and our soul needs time to grow, just like the plants. Our day will come.’ He lets Louis’s remarks pass and hacks at the dry soil, his thoughts seemingly elsewhere.

At noon, when the sun has reached its height, a shrill whistle sounds signalling a much earned break. Tula and Louis make their way to the side of the field and settle in the shade of a divi-divi tree where they’re joined by slaves from other parts of the field. A man with a wheelbarrow can be seen slowly making his way towards them along a dirt track. The bomba straddles the track in a temper and roars at the man.

‘Quaku, you’re late again. When the whistle blows you have to be here right away. Get a damn move on! This is your last warning.’ Tula looks up. Why’s he picking on my little brother? He’s doing his best, isn’t he? Quaku might be slow, but you certainly can’t say he doesn’t make an effort.

‘Leave him alone. He can’t help it.’ The words are out before Tula realises it. The bomba lunges at him in the blink of an eye and grabs him by the neck.

‘He can’t help it? So do you expect me to do it myself?’ he hisses in Tula’s ear. ‘Quaku, get over here, right now.’

Quaku lumbers towards the bomba slowly, dragging his left leg, his shoulders hunched as if struggling to support his slightly oversized head. A twinge of compassion shoots through Tula’s soul. Poor Quaku. He tries so hard. The master almost tossed him into the sea the day he was born, but Jorboe and Rosita begged to have him spared and promised they would take care of him and make sure he wasn’t a burden to anyone. He grew into a cheerful boy who followed Tula wherever he went, like a shadow. He felt safe with Tula around, or better said, with Tula and Louis. When the boys got into trouble, say for firing kenepas with their catapults ‘by accident’ at the bigger boys in the village, it may have been Louis who settled the fight that inevitably followed, but it was Tula with his sweet talk who managed to stave off punishment when the bigger boys’ parents came complaining. Before they even had the chance to talk to their father, Tula would go knocking and apologise, or tell them his side of the story. He was so good at it, he often managed to win them over and even leave them feeling sorry for him. And Quaku would invariably pull an innocent face with those big endearing eyes of his, enough to melt anyone’s heart. It got them out of plenty of trouble. Jorboe was usually protective of Tula, but he could be strict if he had to.

Quaku looks up, stares at the bomba in shock, saliva dripping from the corner of his crooked mouth, a puzzled grin adorning his face.

‘Quaku, do you know what your job is?’ the bomba sneers.

‘Bbbring f-food?’

‘Bring food, master!’ the bomba snarls

‘Bbbring food, ma ma ma…’

‘Never mind, boy,’ says the bomba, exaggeratedly friendly all of a sudden. ‘You’re not up to bringing the food, are you. Just as you’re not up to bringing it on time, eh? Let’s find something else for you to do, something you can manage. From now on you can join your brother out in the field.’ He grins at Tula. ‘Go on then, go join your brother.’ Quaku nods nervously and limps towards the men gathered in the shade of the tree.

Then the bomba addresses the entire group. ‘I have news! You’ll have noticed that the harvest has been pretty meagre this year, not enough to feed you all. And I don’t have to tell you that you only have yourselves to blame. If it was up to me you’d have to put up with rations equal to what you bring in, but the master has decided in his infinite goodness to give you all another chance.’ He falls silent for a moment.

‘From now on you’ll be working Sundays on San Juan.’ The men turn to one another in astonishment and a disapproving murmur runs through the group.

‘And to make things even better, you’ll be getting paid for it,’ the bomba continues.

Tula is surprised. Working for money? Good news indeed. Money means a lot in this world. With money you can buy a plot of land for yourself, and keep the best part of whatever you produce. Everyone has heard stories about the slaves in the city who earned enough money to buy their own freedom. Now they’re their own master. Working for money? Tula can hardly believe his ears.

‘And with that money from now on you will buy your own food, from the storehouse here on the plantation.’

The murmuring stops immediately and the long silence that follows is only interrupted by the brash squawk of an oriole. Tula’s about to explode with indignation. The only day in the week we have to recover a little from all our hard work. The only day we have time to spend with the other villagers, and the master wants to take it from us. Just like that! Tula gets to his feet.

‘Isn’t it true that the master is obliged to give us food?’ He stares the bomba in the eye unashamedly. ‘Isn’t it true that the master is responsible for clothing, a

cabin to sleep in and enough food to keep us alive?’

Tula turns to the men under the tree and lifts his voice: ‘We don’t have to accept this! The master has a duty…’

The lash digs deep into his back as two men grab hold of him and work him to the ground.

‘The master has a duty to keep people like you calm. Take him! We’ll see how much big talk he has left in him later.’

IV

As evening falls, a downcast Jorboe stares in the half-light at the smouldering fire in front of his cabin. ‘The whites are in charge in this world, Tula, that’s just the way it is. There’s no point in fighting it.’ Tula winces as Rosita dabs his back with a mixture of healing herbs. But the searing pain isn’t enough to dispel his unabated indignation.

‘It’s their own law, Papi. All I did was remind them about it.’

Jorboe squats in front of his son and fixes his eyes on him.

‘So who do you think their laws are for, boy? To protect us, or to give the masters the right to treat us however they please? Forget it, Tula. If the masters’ laws get in the way they just change them. That’s the way it’s always been and that’s the way it’s always going to be.’

Tula turns away. How can his father be so resigned? Has he no pride? He’s the senior elder in the village. How can he let this pass? The injustice they have to face, day in day out. He lashes back, his voice choked with rage.

‘Do we have to just take it all, just put up with it? Look at what they’re doing to us, how they treat us. God made us all equal, but here on earth the whites think they’re in charge, in control.’

‘But they are in control, Tula. It’s time you got that into your head!’ Rosita intervenes.

‘And be careful what you say and who you say it to. Me and your father don’t want to lose you, boy.’

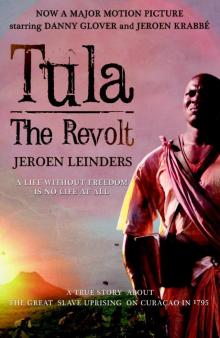

Tula

Tula